- Home

- Sherry Thomas

The Hidden Blade Page 7

The Hidden Blade Read online

Page 7

To Sir Curtis, absolutely nothing, which gave Leighton a savage pleasure.

Father also named Mother and Mr. Henry Knightly, Mother’s cousin, as Leighton and Herb’s guardians. Again, a deliberate repudiation of Sir Curtis. Leighton was almost giddy—until he remembered Sir Curtis’s smugness, looking into the nursery.

But what could Sir Curtis do? He did not hold their purse strings and he had not been appointed guardian.

Sir Curtis, however, did not seem the least bit upset by the reading of the will. After the servants and the solicitor had vacated the library, he strolled to the ivory-inlay console table where Father’s decanter was kept and tapped a finger on the crystal topper.

“Any fortification for you, Mrs. Atwood? And you, Mr. Gordon?”

They both shook their heads, Mother uncomfortable but stoic, Herb stone-faced but unafraid. Like Leighton, they had been bolstered by the contents of Father’s will.

“Well, then, we will start with you, Mrs. Atwood—ladies first.” Sir Curtis gave a thin-lipped smile. “You are an utterly useless woman.”

Mother flinched. Leighton gritted his teeth.

“Get out,” said Herb. “You will not insult a lady in her own home. And there is nothing more for you to do here.”

“So speaks the man who might as well have pulled the trigger on my brother,” said Sir Curtis coldly.

Herb swallowed.

Sir Curtis turned back to Mother. “It is the role of the wife to uphold the vows of marriage and the sanctity of the family. But you, Mrs. Atwood, you had no strength and no conviction. You chose to seek your own pleasures and left your husband vulnerable to temptation. A better woman would have guarded him and kept him safe for as long as she and he both lived. But you, full of weakness and selfishness, abandoned your duties long ago.”

Each of his words seemed to strike a blow upon Mother, who shrank and shrank.

Leighton saw now that he had been blind, that Father’s death had left Mother badly shaken. Had she been blaming herself the way he blamed himself? Had she been wondering whether things would have been different if only she hadn’t been so far away from home when Sir Curtis unexpectedly arrived?

“Do you actually think I will let an unrepentant adulteress be guardian to my nephew? Don’t act so surprised. When he died did you think I did not notice you were not at home? Did you think I did not find out that one week out of every month you took that other child of yours and left on some supposed trip to visit elderly relations? And from then on, did you think it was all that difficult to find out about the tall, blond Californian?”

Mother spoke, her voice almost choked, but defiant. “It doesn’t matter. There is nothing you can do.”

“To the contrary, there is a great deal that I can do. No doubt my brother believed your cousin Mr. Knightly to possess not only robust health, but a sterling character. I suppose you neglected to inform him that Mr. Knightly had been sent down from university for forging cheques?”

“That was more than twenty years ago, and for all of five pounds!” cried Mother. “It was only a youthful prank—Henry just wanted to see whether it could be done.”

“But how can we be sure such deceit has been eradicated from his character? Not to mention that Mr. Knightly is wretchedly poor for a man with a demanding wife and four daughters who will need London seasons very soon. Would the Court of Chancery look kindly upon his fraudulent past? I do not think so. Not when there are substantial rents that come in every month from lands that belong to my nephew, and every opportunity for embezzlement.

“And when I have removed him from this guardianship, I will, of course, ask that I myself be made a coguardian of the boys. You blanch, Mrs. Atwood. Does the thought not please you? You are afraid I will take them from you, are you not? You are wise to fear, for that is exactly what I will do. Nigel did not see fit to punish you for your adultery, but I will.”

Mother emitted a strangled sound.

“You cannot do this!” Herb said heatedly. “No one wants your interference. Nigel has seen to the protection and welfare of his widow and children. He intentionally left you out of his will. Why can’t you respect that?”

Sir Curtis turned to Herb. “Tell me this. Did Nigel beg you not to lead him into temptation? Did he plead for his soul? Did he resist, with what little courage and fortitude he had, the lures of the flesh that you dangled before him?”

Herb fell silent.

“He did, didn’t he? And you overrode his good sense. You overrode his love of God. You brought him to his doom and now you want a say in the welfare of his children?”

“That is not—”

“Shut up, you sodomite wretch. I will deal with you later. Now, where were we, Mrs. Atwood? Ah, yes, your unfitness as wife and mother.”

They had all three been standing. But now Sir Curtis sat down on Father’s favorite padded chair, his hands on the armrests, one ankle over the other knee—completely at ease, every inch the master of the manor.

“I am not inclined to be lenient—leniency serves no purpose except to encourage the delinquent. But I must consider my wife-to-be, who will not wish for a scandal to mar her wedding. So I will offer you a choice, Mrs. Atwood. We can publicly reveal your adulterous conduct and strip you of your guardianship via sworn statements in the Court of Chancery, or we can resolve this privately. You take your bastard child and leave the country altogether. Invent some excuses. Say that his health is frail and must need the sunshine and mildness of California. Once you are far away, you may marry your paramour or continue to consort with him in sin. It will no longer be my concern.”

“But Leighton—”

“My nephew, who is very much my concern, will come under my guidance.”

“No!”

“Think carefully. You have acted foolishly and arrogantly and you are about to pay the price. Now the question is only, Will you pay with one of your children, or both? Remember, the other boy is not my flesh and blood. Now leave us and consider your choices. Go.”

The door closed behind Mother.

Leighton shook.

He had met Cousin Knightly a few times, a short, bald fellow full of glee and laughter. His daughters adored him, though he could not buy them new dresses or fashionable hats. His wife complained loudly of their poverty, but even she, Leighton thought, was in truth quite fond of her husband.

And now Leighton would lose a good-natured guardian for a five-pound forged cheque from before he was born.

“So,” said Sir Curtis, “you have not ended your miserable existence yet.”

Herb started—Leighton had not passed on Sir Curtis’s command for him to kill himself. “I have no intention of ever taking my own life.”

“Hmm. Let me tell you about your other choice then. There is a grieving mother whose son died of an overdose of chloral. She blames his death on the fact that he had recently been spurned. By another man. The homosexuality of the liaison does not bother her—one of those stupid women who can never find a single fault with her own child—but she is out for blood against that man.

“Only she does not know his identity. I, however, have decided that you are that man, Mr. Gordon. It will be quite easy for me to convince her of that, as you and her son do frequent similar circles. And then it will be only a minor step to have her go to the police and report you for the deviant you are.”

“But others will be able to testify that I do not know her son.”

“In the end it would not matter. It will be about whether you have committed the kind of perverted acts that the law condemns. And it really is too bad that you will receive only a prison sentence, and not a trip to the gallows.”

“You can’t do that,” said Herb, but he sounded impotent.

“I can and I will,” answered Sir Curtis, anticipation in every syllable. “And I will enjoy your downfall, Mr. Gordon. So it is up to you: a quick, private end or months of public humiliation followed by years of misery.

“This just

came back from the inquest. It would be poetic justice, wouldn’t it?” He opened a case on the library desk, which contained a pair of antique dueling pistols. Leighton recoiled—Father had used one of the pistols to take his own life. “Hell now or hell on earth. Make your choice, Mr. Gordon.”

Sir Curtis left. Slowly, as if sleepwalking, Herb approached the desk and picked up the pistol that was still marred by bloodstains.

“No!” Leighton cried.

Herb, startled, looked up.

Leighton ran down the circular stairs. “Please don’t even think about it.”

Herb gently set down the pistol. “I wasn’t. I promise I wasn’t—not seriously, in any case. I was thinking more of your father. How desperate he must have felt, how terrified, to resort to such a measure.”

Anguish weighed down his words.

“It isn’t your fault,” Leighton told him. “Father—he loved every moment he had with you.”

Moisture glistened in Herb’s eyes. “And I him. And I loved coming here. I loved spending time together, all three of us.”

He settled his hands on Leighton’s shoulders. “Please don’t ever think he meant to abandon you—or anyone else he loved. Sometimes it’s hard to think clearly when you are in a panic. I wish he’d drunk himself to a stupor instead, or smashed up a room—anything but this.”

Leighton was shocked. It had never occurred to him that something as grave and irreversible as suicide could have been a moment’s impulse.

“Believe me, I’ve had friends who have jumped from bridges and then never did anything to endanger their own lives again. If only…There are so many if-onlys, aren’t there? The important thing to remember is that he never meant to leave you unprotected. He loved you very much, and he was infinitely proud of you.”

“He loved you too. He wouldn’t want you to listen to anything Sir Curtis says.”

Herb glanced at the pistol on the desk. “I’m afraid that man isn’t bluffing.”

Sir Curtis would probably consider it an affront to his honor and capability to bluff. No, he was a man of action. The right hand of God. “But he doesn’t have infinite reach. You can leave the country. You haven’t committed any kind of crime that would make the law chase you over international borders.”

Herb exhaled. “Where would I go?”

“Anywhere. As long as you will be safe.”

“Then come with me. We’ll run away together. We’ll travel all the way to China and search for the monks’ treasure.”

And what a wonderful adventure that would have been, under different circumstances. Leighton felt a hot prickle in his eyes. “How much do you think a Buddha statue made of pure gold would weigh?”

“Anything bigger than the size of a bust and the two of us might not be able to lift it.”

“We’ll have to get stronger fast,” said Leighton.

They laughed, a sound Leighton hadn’t heard in ages.

Tears fell down Herb’s face. All at once he looked crumpled, a man with everything taken out of him. “I don’t know what I’m going to do. It was largely my fault—I couldn’t leave well enough alone and had to have everything. How can I live with myself, knowing the calamity I had caused?”

Leighton could not stop his own tears. “It wasn’t your fault, and please don’t ever think so again. If you believed that, Father would never be able to rest in peace.”

Herb gripped Leighton’s arms. “Come with me. Your father would have wanted me to look after you.”

Leighton wanted that more than anything else. “That would set Sir Curtis and the law after you, for the abduction of a minor.”

Herb laughed bitterly. “There is that, isn’t there? I can’t seem to do anything right these days.”

“Just look after yourself for me. I need to know that you are safe—and well. Can you do that for me, please?”

More tears fell down Herb’s face. “I will, my dear boy. I will do anything you ask.”

Mother was in the solarium, standing before the window, a handkerchief crumpled between her fingers. She turned around at the sound of Leighton’s entrance. Her face was pale against the black crape of her mourning gown, the rim of her eyes red.

“Leighton, my dear,” she said softly.

They used to walk together in the gardens, Mother and Father. In the evenings they took turns reading books aloud to each other. And from time to time Leighton would catch Mother looking at Father wistfully, as if remembering him—or herself—from a different time.

Father had loved her too, a gentle, respectful love tinged with traces of regret.

And Leighton would take care of her—by removing her and Marland from Sir Curtis’s sphere of influence. Except he didn’t quite know how to go about it. From time to time Mother could be stubborn. If she was determined to stay and protect Leighton…

“I heard what Sir Curtis said to you after the reading of the will,” he told her. “I heard him tell you to take Marland and go.”

She squared her shoulders. “I will not. I will not leave you alone with that monster.”

His hand closed around the door handle. He could try to reason with her about how the monster would terrorize Marland, but he didn’t think she would hear him.

“So you do not dispute anything that was said?” he said, making his voice cold.

She swallowed. “No, I do not dispute it. Please understand, Leighton, that—”

“So that’s what you had been doing all these years—neglecting Father, neglecting me, and neglecting everything else to sin with your illicit lover.”

She flinched as if he had slapped her.

He forced himself to continue, speaking as if he were Sir Curtis himself. “And no wonder Marland has such anemic looks. He isn’t even an Atwood. How do you live with yourself? The forty thousand pounds Father settled on him should have been mine. That is money you—and he—stole directly from me.”

“That has never been my intention in the slightest!”

“And yet you plan to continue living in my home, on my income, and to go on saddling me with the expenses of raising a parasite.”

Her hand came up to her throat. Her fingers shook. “I thought you loved Marland. I thought you loved—”

I thought you loved me. Except she couldn’t bring herself to say it.

Herb was wrong. Leighton was not kind—he was capable of all kinds of atrocities.

“Do we…do we really disgust you so much?” Mother’s voice had become barely above a whisper.

“You have no idea how ashamed I am to be related to you and that child of yours.”

Her hand closed into a fist. He fully expected her to hit him.

“If you really feel so,” she said, her voice hoarse, defeated, “if you really feel so, then perhaps Marland and I ought to go.”

Why did she not realize that no trespass on her part could ever equal the cruelty he displayed now? Why did she let him ride roughshod over her with his trumped-up moral outrage, when she ought to strike him for his utter want of propriety and respect?

Why did the good people of the world so meekly allow themselves to be ill treated and trampled over?

“Yes,” he said, “I feel so. Very strongly. Very, very strongly.”

Mother and Marland left the next morning. Marland cried and struggled. It took both Mother and his nursemaid to force him into his carriage.

Leighton did not wave good-bye. He gazed somewhere above his brother’s red, bawling face. They had gone to Father’s grave at the crack of dawn and made a honeysuckle wreath together. He would remember that instead, and Marland’s plump little hands gently patting the mound of earth on which they had placed the wreath.

Sleep tight, Marland had said to Father. Sleep tight.

Deep in the big trunk that held many of Mother’s books, Leighton had hidden a package that contained everything he could not bear for Sir Curtis to get his hands on: hundreds of photographs, just as many letters from Herb, and, of course, the beautiful

jade tablet that had been wretchedly difficult for him to let go of.

He had tried to write a letter, to explain and to apologize. In the end he had burned all his drafts. Better for Mother to believe that he was as monstrous and callous as Sir Curtis. She would be safer that way, and Marland too.

The carriage clattered along the drive, becoming smaller and smaller. Then it was gone.

And he was all alone.

Chapter 7

The Apprentice

Mother studied the finely textured shuen paper spread on her desk. She had finished the background of a new ink painting, a mountain with ridges sharp as swords.

Ying-ying had been grinding ink for her. Now she picked up the massage roller made of polished agate and applied it to just beneath Mother’s shoulders.

Mother glanced back, astonished. “When did you become such an example of filial piety?”

Ying-ying didn’t say anything. When she looked upon Mother now, the sensation in her heart was very nearly one of pain. Several times alone in her room she’d broken down in tears as she imagined what Mother must have gone through in those darkest days of her life.

She was at once beyond happy for her—that she had found peace, quiet, and security at last—and beyond frightened that it wouldn’t last.

“Does Da-ren like paintings?” she asked.

She had always been curious about Da-ren, but she could not remember the last time she’d posed a question about him directly to Mother.

Mother picked up a smaller brush and dipped it in the ink Ying-ying had freshly made. “I suppose he would, if he had time for such things.”

Ying-ying set down the roller and returned to her station beside the ink stone. “Why is he so busy?”

“Well, he is an important adviser at court. And he has many ideas for…reforms.” Her tone turned slightly grim as she uttered the last word.

_preview.jpg) Claiming the Duchess (Fitzhugh Trilogy Book 0.5)

Claiming the Duchess (Fitzhugh Trilogy Book 0.5) The Art of Theft

The Art of Theft The Magnolia Sword: A Ballad of Mulan

The Magnolia Sword: A Ballad of Mulan A Study In Scarlet Women

A Study In Scarlet Women The Hollow of Fear

The Hollow of Fear The Magnolia Sword

The Magnolia Sword Beguiling the Beauty ft-1

Beguiling the Beauty ft-1 The Heart is a Universe

The Heart is a Universe The Hidden Blade: A Prequel to My Beautiful Enemy (Heart of Blade)

The Hidden Blade: A Prequel to My Beautiful Enemy (Heart of Blade) Ravishing the Heiress ft-2

Ravishing the Heiress ft-2 The Immortal Heights

The Immortal Heights The Hidden Blade

The Hidden Blade Ravishing the Heiress

Ravishing the Heiress Tempting the Bride

Tempting the Bride The Luckiest Lady in London

The Luckiest Lady in London The Bride of Larkspear: A Fitzhugh Trilogy Erotic Novella

The Bride of Larkspear: A Fitzhugh Trilogy Erotic Novella Claiming the Duchess

Claiming the Duchess The One in My Heart

The One in My Heart His At Night

His At Night A Dance in Moonlight

A Dance in Moonlight A Conspiracy in Belgravia

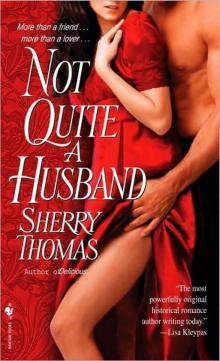

A Conspiracy in Belgravia Not Quite a Husband

Not Quite a Husband