- Home

- Sherry Thomas

The Hidden Blade: A Prequel to My Beautiful Enemy (Heart of Blade)

The Hidden Blade: A Prequel to My Beautiful Enemy (Heart of Blade) Read online

Table of Contents

Dedication

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-one

Chapter Twenty-two

Chapter Twenty-three

Chapter Twenty-four

About the Author

My Beautiful Enemy: Excerpt

More books by Sherry Thomas

Copyright

Dedication

To my dear friend Flora, with whom I spent some of the happiest hours of my life reading and talking about our favorite wuxia stories

Chapter 1

The Photograph

Peking

The twelfth year of the reign of the Tung-chih Emperor (1873)

The foreign devil stared at Ying-ying.

He was the size of her thumb, yet she had trouble holding his gaze. She looked away from his eyes. In the fading photograph, his strangely tight-fitting garments were the brown of eggs cooked in soy sauce, his white skin the color of weathered bamboo. His nose protruded proudly, like the prow of a foreign-devil warship. Thin, colorless lips twisted into a half sneer.

His hair was a darkish shade, cut short, parted on the side, and combed slick. He had neither beard nor mustache, but the same hair that grew on his head extended down the sides of his face almost right to the corners of his lips, like a forest throwing out two spurs of itself down the slope of a mountain.

He did not stand straight, but rather leaned to one side, his left foot propped on a stool, one black shoe gleaming. To the other side of the stool, a woman sat with her profile to Ying-ying, head bent, a large book open on her lap. She wore a ridiculous contraption: her sleeves the size of rice sacks, her skirts a tent large enough to sleep two.

What stupid, impractical things the foreign devil women wore.

Ying-ying’s breath caught in her throat. She leaned in closer. She had been distracted by the clothes, but the woman was no foreign devil.

It was Mother.

In her shock Ying-ying almost didn’t hear the footsteps coming into the courtyard. She tossed the photograph into its redwood box and shoved the box under Mother’s fox fur-lined winter cape.

Dropping the lid of the great trunk, she dashed out to the study and settled into her chair just as Mother’s maid came through the doors of the front room. The rooms were stretched against the wall of the courtyard like cubes of lamb on a shish kebab, in one straight row.

Ying-ying grabbed the writing brush she had left resting on the ink stone and pretended to smooth out excess drops of ink against the rim.

“Bai Gu-niang studying so hard?” The maid, Little Plum, teased her gently as she went past. Bai was Ying-ying’s family name, gu-niang the respectful address for a young lady. “Little girls as pretty as you don’t need to know the classics.”

“Has Boss Wu left already?” The silk merchant had arrived only half an incense stick ago.

“They are still drinking tea—he hasn’t even had his apprentice bring in the wares yet. Fu-ren sent me to fetch her new fan. She wants to see if Boss Wu has something that will go with it.” The servants referred to Mother as fu-ren, her ladyship. Little Plum paused as she located the desired fan. “But she did say to tell you she will expect at least five sheets done when she returns.”

Ying-ying moaned. “My wrist will hurt all night.”

“Amah will give you an herbal compress.” Little Plum laughed as she sauntered out.

Ying-ying was back in the bedchamber in a second, digging through the trunk again.

Nosing through Mother’s rooms had become a clandestine hobby of late. It had started when she had been tasked to fetch a supply of paper for Mother’s ink paintings. In the study cabinet where she had found the paper, she had also come across a collection of curious ink stones, some big as a plate, others small enough to fit into her palm. Her delight in the ink stones led her to discover troves of vermilion-stained seals, packets of incense from Japan, and a dozen tiny spoons used for ladling water onto the stone to facilitate the grinding of the ink stick.

It had been most natural, after she had exhausted the study, to move on to Mother’s inner rooms. There she peeked at Mother’s jewels of jade and pearls and sniffed her tiny pots of rouge and powder.

But she had never unearthed anything like the contents of the redwood box.

There were other items inside: an oval ivory bauble that did not seem to be a hair ornament, a flexible jewel-encrusted band of gold, a small booklet that had been cut and sewn by hand, with each page devoted to two strange symbols, sometimes identical, sometimes not, and a sheet of paper with foreign writing on it.

It was the photograph, however, that drew her, like a toddler to the edge of a deep pond.

Mother was concubine to a very important Manchu. Everyone addressed him simply as Da-ren, great personage. He was a prince of the blood and an uncle to the current emperor, but he was not Ying-ying’s father.

Who her father was she did not know—and did not ask. Harsh rebukes, received during the earliest years of her childhood, barely remembered but deeply ingrained, made her forbear from ever raising that unwelcome question.

Yet she had always pondered, when she had nothing else to distract her.

And now here was this man, by whose side Mother sat all trussed up in a foreign devil costume, as meek as an oft-fed rabbit.

But he was a foreign devil. A foreign devil! She shuddered. Greedy, bloodthirsty creatures they were, coming from their savage lands with their terrible manners and their blazing cannons. She had even heard whispers that they ate babies.

No, whoever this man was, he was no more blood relation to her than Da-ren.

However, as she raised her head, she saw her own eyes reflected in a small standing mirror on Mother’s vanity table. Her irises were not black, nor even brown. Rather, they were a deep, opaque gray-blue, the color of a desolate sky about to unleash a great storm.

She gasped—there was another face in the mirror.

“Put everything back,” remonstrated her amah.

How did Amah come up to her without her detecting anything? A curtain of ceramic beads hung in the doorway. The beads clinked whenever anyone passed through. And Ying-ying had keen ears, rabbit ears. She could hear a door open and close three courtyards away.

“I was just looking for a handkerchief,” she lied as she buried the redwood box in the depths of the trunk.

She was pulled up by the shoulder. Amah pointed to her chest. “What’s that?”

It was her handkerchief, snugly tucked at the closure of her blouse, one corner artfully peeking out.

“Don’t go poking where you have no business,” Amah warned. “Now go practice your calligraphy.”

Mother was not entirely pleased with Ying-ying’s output. She frowned as she examined Ying-ying’s copy of a great ancient calligrapher’s work. Ying-ying resigned herself to the criticism to come. Her characters, alas, always looked somewhat undernourished.

Mother, on the other hand, could do marvelous things with a brush. The couple

t on either side of the study doorway she had written herself: The lamp shines gently in the quiet mountain room; steady rain falls upon the cold chrysanthemum bloom. Each character on the gold-speckled rose paper was manifest elegance, the strokes measured and meticulous, the balance immaculate—flawlessly, decorously beautiful, just like Mother.

In fact, the entirety of her home was a reflection of her. In paintings, a beautiful woman was never surrounded by too many things; a few choice blossoms and a dancing willow branch set her off perfectly. And so it was with Mother. Her rooms, with their graceful but spare furnishings, formed a comely but muted backdrop for her, whose exquisiteness reigned unrivaled.

To Ying-ying’s surprise, Mother didn’t say anything as she handed the calligraphy sheets back. Only then did Ying-ying notice that she looked wan despite the rouge on her cheeks.

“Little Plum, help me to bed,” Mother called. Then, to Ying-ying, “Tell your amah to make some more of that cough potion for me.”

Mother’s tiny feet made it difficult for her to walk, but she managed to turn her wobbly progress into something almost like a dance, a sprig of peach blossom swaying in the wind. Ying-ying always liked to watch her walk.

But as soon as Little Plum reached her chair, Mother began to cough. She twisted her torso to one side, dropped her head delicately, unfurled her handkerchief as if it were a flower bud come to bloom, and made almost no noise at all. Her handkerchiefs were once pink or yellow, but since the coughing started, she carried only those of deep red, so the droplets of blood wouldn’t show.

One of Little Plum’s cousins had died the year before. First he coughed; then he coughed up bits of blood; then he coughed up rivers of blood; soon there was nothing any doctor could do for him. Ying-ying had heard it all in the kitchen, between visits from Little Plum’s relatives.

She hurried out to find Amah.

In the next courtyard, along the north-facing side, Amah had fitted out a small room expressly for the purpose of brewing medicinal potions. The far end of the room was taken up by a kang, a raised brick platform so arranged with flues that a small brazier placed inside could warm the whole of it. There were kangs in a great many rooms of their dwelling. Ying-ying slept on one. Mother thought them ugly and had those in her rooms dismantled. But Mother was a southerner. According to Cook, southerners valued appearance above comfort, even health.

The rest of the room was arranged almost like an apothecary’s. Ceramic jars of dried herbs and flowers crowded the shelves that lined the walls. A bench next to the kang held clay pots and lidded bowls. Amah sat in the center of the room before a tiny potbellied stove, already making the requested potion, judging by the bitter aroma wafting in the air.

“How do you know she needs it?” Ying-ying took a stool and sat down next to her.

Amah gave Ying-ying a woven straw fan so she could make herself useful. As Ying-ying fanned the flames, Amah stirred the bubbling brown stew of loquat leaf, bellflower root, licorice, and ginger. “It’s the fourteenth. Da-ren comes in two days. She always wants to dampen that cough before he comes.”

They settled into a busy silence as Ying-ying found a suitable rhythm to her fanning. Like Mother, Amah was from the south. But unlike Mother, who quite intimidated Ying-ying with her great beauty and equally impressive talents, Amah posed no discomfort. She was as plain as a common moth, though she kept herself trim and neat. And her talents Ying-ying simply adored.

Amah could capture any insect. In spring she gathered butterflies. In summer she caught fireflies and crickets, and made sure Ying-ying’s room was free of mosquitoes. Her hands, rough and round-fingered, were nevertheless extraordinarily skilled. She wove animal figures out of reed, sculpted tiny people with bits of colored dough, and from old sticks of candle she carved mock seals for Ying-ying, with titles such as “Princess of the Fragrant Garden,” or “Muse by the Pomegranate Blossom.”

But what the grown-ups most appreciated was her expertise in medicinal herbs. She knew a remedy for every common ailment: tree peony for Cook’s female problems, fenugreek for Little Plum’s stomach pains, cloves and camphor for Mother’s backaches. When Cook’s water-carrier brothers visited in the kitchen, she’d give them a formula of angelica and ephedrine for their joints. Should Little Plum’s aunt drop by, she had just the thing—red peony—for her patchy skin.

In addition, she maintained a greenhouse of sorts, a crude contrivance half dug into the ground, with a low mud wall and slanting frames covered with Korean paper. In the dead winter months, with the addition of a tiny smudge stove, she was able to produce fresh flowers for Mother’s coiffure and green herbs for Cook.

“It’s almost done,” Amah said, giving the brew one last stir.

Ying-ying fetched a bowl. Amah poured nearly to the rim and covered the bowl tightly.

Ying-ying ventured to speak something of what had transpired earlier in the afternoon. “You won’t tell Mother, right?”

“No,” Amah answered without looking at her. “But what you did was still stupid.”

Ying-ying blushed. “I wasn’t stealing. I just wanted to see what she had.”

“Don’t go around digging in other people’s things,” Amah said darkly. “Dig long enough and you’ll always find things you wish you hadn’t.”

On her way to Mother’s rooms with the potion, Ying-ying chewed over Amah’s words. Amah had seen the photograph—how could she not, materializing directly behind Ying-ying? If so, did what she said just now confirm the worst of Ying-ying’s suspicions?

Was the foreign devil her father?

Chapter 2

The Rift

Sussex, England

The forty-sixth year of Queen Victoria’s reign (1873)

“Legend has it that this is the key to a great treasure,” said Herb, lifting up the tablet of translucent white jade.

The tablet was about six inches long, four inches wide, and barely a quarter inch in thickness. Upon it a bas-relief goddess danced, her back arched, her eyes closed. To either side of the goddess were characters in intricate Chinese script. But whereas the goddess was all billowing sleeves and trailing ribbons, the words—to Leighton Atwood’s untrained eyes, at least—gave an impression of solidity and wisdom.

There were other antiques at Starling Manor—suits of armor from the War of the Roses, tapestries that predated the Renaissance by hundreds of years, and, according to family lore, a jewel-encrusted goblet from which Queen Elizabeth once drank. But here in the library, in the midst of a collection of six thousand volumes, there was only this single artifact from faraway China, kept in a special display case near Father’s favorite reading chair.

Herb held the tablet toward the light of the chandelier. The tablet seemed to glow from within, a soft, rich radiance. “Mutton-fat jade, they call it, for its density and creaminess.”

He returned the jade tablet to its glass-topped display case and glanced at Father. “A rare and beautiful thing, would you not agree, Nigel?”

The tropical sun, Leighton often thought, must be something like Herb, an entity of unfailing cheer and warmth. Which made it all the more disconcerting to hear the prickliness in Herb’s tone.

“Of course I agree,” Father answered, his words placating—and slightly anxious.

Father was often anxious, but never when Herb was around. With Herb he was just…happy. It was impossible to be anything else in Herb’s company, or so Leighton had always thought.

Until now.

“Would you not tell the legend behind the jade tablet, old chap?” asked Father. “Leighton always enjoys hearing it. Is that not so, Leighton?”

“Yes, sir,” answered Leighton, all too aware of the note of uncertainty in his own voice.

It was usually Leighton who asked to hear the legend, and Father who teased that he must have already heard it dozens of times.

Herb turned toward Leighton. He had a lanky build, blond hair, and a deceptively young face that sometimes made Leighton forget that h

e was not a youth but a grown man of twenty-seven, far closer in age to Father’s thirty-two than to Leighton’s not-quite eleven.

“The legend,” Herb murmured. He smiled, a rueful, almost apologetic smile, as if he sensed the uneasiness he had caused Leighton. “All right, the legend. Tell me, Leighton, where did Taoism originate?”

Father untensed. Leighton released a breath he had not known he was holding. “In China.”

“And Buddhism?”

“India.”

“Which means…” Herb prompted.

“That for China, Taoism is indigenous, whereas Buddhism is an import,” said Leighton.

“Exactly,” said Herb. “Toward the latter years of the Tang Dynasty, there was a Chinese emperor who strongly favored Taoism. The Taoists who promised him elixirs of immortality urged him to promote their religion and suppress the practice of Buddhism, which they viewed as a foreign upstart.

“The Buddhist monks of China began to fear that their monasteries would be demolished and their wealth seized. Such wealth—a mountain’s worth of silver ingots, Buddha figures of pure gold, not to mention priceless paintings and calligraphic scrolls.”

At this point Father would usually—and with great affection—ask Herb how much he had embellished the story. Herb would reply that he had added no sensational details, as the story had come to him already feverishly embroidered.

But tonight Father only listened, a glass of whisky clutched in his hand.

His attention seemed to gratify Herb, who smiled again. “Well, such valuables must not fall into the emperor’s greedy hands. So from all over the land the monks gathered under the guise of a great scriptural congress, while secretly moving the riches of their cloisters.”

Leighton imagined squat wagon carts stripped to the bone, in order to not leave deep ruts that would give away the weight of the heavy load they carried. There would also have been palanquins in which the venerable abbeys of the monasteries purportedly sat, carried by the strongest monks. Except only gold and jade rode inside the palanquins; the venerable abbeys, in their plainest robes, dusty and road-weary, walked alongside the humblest of initiates.

_preview.jpg) Claiming the Duchess (Fitzhugh Trilogy Book 0.5)

Claiming the Duchess (Fitzhugh Trilogy Book 0.5) The Art of Theft

The Art of Theft The Magnolia Sword: A Ballad of Mulan

The Magnolia Sword: A Ballad of Mulan A Study In Scarlet Women

A Study In Scarlet Women The Hollow of Fear

The Hollow of Fear The Magnolia Sword

The Magnolia Sword Beguiling the Beauty ft-1

Beguiling the Beauty ft-1 The Heart is a Universe

The Heart is a Universe The Hidden Blade: A Prequel to My Beautiful Enemy (Heart of Blade)

The Hidden Blade: A Prequel to My Beautiful Enemy (Heart of Blade) Ravishing the Heiress ft-2

Ravishing the Heiress ft-2 The Immortal Heights

The Immortal Heights The Hidden Blade

The Hidden Blade Ravishing the Heiress

Ravishing the Heiress Tempting the Bride

Tempting the Bride The Luckiest Lady in London

The Luckiest Lady in London The Bride of Larkspear: A Fitzhugh Trilogy Erotic Novella

The Bride of Larkspear: A Fitzhugh Trilogy Erotic Novella Claiming the Duchess

Claiming the Duchess The One in My Heart

The One in My Heart His At Night

His At Night A Dance in Moonlight

A Dance in Moonlight A Conspiracy in Belgravia

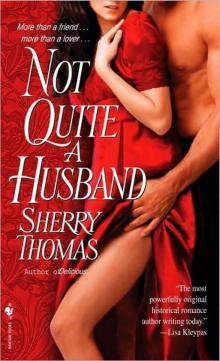

A Conspiracy in Belgravia Not Quite a Husband

Not Quite a Husband