- Home

- Sherry Thomas

The Immortal Heights Page 7

The Immortal Heights Read online

Page 7

“Yes, monsieur. Such a lovely gentleman. He will be glad to see you, monsieur.”

Horatio Haywood was indeed overjoyed as he opened the door. But his smile wavered when he realized that Titus had come alone.

“She is fine,” Titus said quickly. “May I come in?”

“Yes, of course. Do please forgive me, Your Highness.”

He was shown to the salle de séjour, with its enormous paintings of nonmages frolicking in the countryside. Haywood ran to the kitchen and came back with a tea service and plates of puff pastry with savory fillings.

The man would probably have gone to the kitchen again to fetch more things, but Titus bade him take a seat and recounted what had happened since they were all last in a room together: the real story behind Wintervale’s spectacular display of elemental power, their hasty departure from Eton, and their few but eventful days in the Sahara Desert.

“When I left earlier today she was safe and well, or at least as well as could be under the circumstances. And I trust that our friend is looking after her to the utmost of his considerable ability—although at any given moment she could be looking after him, for all we know. She is very good at keeping her friends alive and in one piece.”

“Fortune shield me,” murmured Haywood. “I was worried—I thought she would have come to see me again, but I never anticipated that so much could have happened.”

They were quiet for some time. “So you remember everything now?” asked Titus.

The older man nodded slowly. “Yes, sire.”

He would have been able to guess at Lady Callista’s betrayal, judging by what they had learned the day they found him at Claridge’s Hotel in London. But to be engulfed by a tide of memories, to remember the fervor of love that had driven him to lie, cheat, and steal for her only to be abandoned so completely—Titus could not imagine his anguish.

His regrets.

“I would like to ask you a question, if I may.”

“Certainly, sire.”

“I can piece together most of the story, even if the details are somewhat sketchy. But one part puzzles me. What is Commander Rainstone’s role in all this?”

Commander Rainstone was the crown’s chief security adviser. She had also, at one point, served under the late Princess Ariadne, Titus’s mother.

“You said she introduced you to Lady Callista,” Titus went on. “I understand Commander Rainstone comes from a humble background. How did she and Lady Callista become friends?”

“Oh,” said Haywood, taken aback. “You didn’t know, sire? Commander Rainstone and Lady Callista are half sisters.”

Iolanthe and Kashkari did not risk flying into Cairo, which had its share of mage Exiles. And where there was a substantial gathering of mage Exiles, there were informants and agents of Atlantis.

Nor did Kashkari want them to walk in each carrying a carpet. They had covered the distance from Luxor to Cairo on travel carpets, but they still had their battle carpets, which were much more substantial in thickness and could not be folded into tiny squares and shoved into pockets. He feared that even rolled up, those carpets might still signal their mage origins.

Instead he bought a donkey on the outskirts of the city and laid their battle carpets across the donkey’s back. He offered the donkey to Iolanthe, but she declined firmly: she’d much rather walk than wrestle with an unfamiliar beast.

So Kashkari rode and Iolanthe walked behind him, her face largely hidden beneath her keffiyeh. The buildings they passed were like none she had ever seen, with each story projecting farther out than the one immediately below. Two top-floor residents on opposite sides of a narrow street could almost embrace across what little distance remained between them.

Their destination was a clean and hospitable guest house. The proprietor embraced Kashkari and greeted him by name. Sweets and cups of coffee appeared as soon as they’d entered their room, followed by bowls of a delicious green soup and heaping plates of dolmas, which were grape leaves wrapped around a savory rice filling.

“You’ve been here before?” she asked Kashkari as they ate.

He nodded, reaching for a dolma. “My brother has been in the Sahara for a while. I would come to visit him every holiday, and it was always a hassle to get me back to school at the end of it. Somebody somewhere might have a mobile dry dock, but there wasn’t always a vessel available—and we couldn’t exactly ask to borrow the emergency boat. So sometimes they could launch me to the Mediterranean and take me to the coast of France. Other times I had to fly back most of the way.

“One day Vasudev had enough of the uncertainty—he also didn’t like me flying so far by myself. He decided to rig me a one-way portal here in Cairo, since most rebel bases had a translocator that could reach Cairo or Tripoli. So we came here and stayed a few days. And then we went to school together, so he could finish the portal’s other end.”

“He visited Eton?”

“Met Mrs. Dawlish and Mrs. Hancock—and Wintervale too. Wintervale and I squired him around the school—walked the playing fields, rowed a bit on the river.”

“He didn’t meet the prince?”

“No, he left before Titus arrived that Half. And it’s a shame you didn’t have the chance to meet him, while we were still in the desert.”

Did the timbre of his voice change? And was it sadness that once again darkened his eyes? The flame of a lantern flickered upon his face and threw his shadow on the wall, against a fretwork panel of arabesque patterns.

She set aside her plate. “What manner of man is he, your brother?”

Kashkari blew out a breath. “He’s a bit shy—our sister, his twin, has always been the vivacious, assertive one. When Amara spoke at the engagement gala, she said that during his first six months at the base he never said anything to her that wasn’t related to equipment production and maintenance.”

“Is that what he is responsible for?”

“He’s a marvel, a true wizard, when you need any devices built, improved upon, or invented from scratch. But don’t let that fool you into thinking he’s only fit for a workshop. He’s also a deadly distance spell-caster—taught me everything I know.”

And Kashkari had been quite the sniper.

“Do you think he and Durga Devi are a good match?”

“They are not an obvious match, but yes, I do think they are good for each other. He needs someone full of life to tear him away from his workbench once in a while. And he is a steadying influence on her, as she can be rash at times.”

Before she could reply, he reached into his pocket. “Will you excuse me?”

He moved away from the divan on which they’d been eating to read his two-way notebook. His expression changed.

Iolanthe rose. “Is everything all right?”

He looked at her, his face now blank. “Vasudev writes that they are married. As of five minutes ago.”

Iolanthe was stunned, and she wasn’t even in love with one of the parties. “I take it today wasn’t when the wedding was scheduled.”

“No, they’d never set a date.”

But she and Titus had brought Atlantis to the rebels’ doorstep. What was the point of waiting longer, when there might not be a tomorrow, let alone a next week?

“I’d better tender my congratulations,” he said.

Impulsively she stepped forward and hugged him. “I’m sorry it wasn’t meant to be. I’m sorry for all the pain this has brought you. And I’m sorry it will hurt worse before it gets better.”

He stood quiet and motionless in her embrace. She let him go, feeling a little self-conscious that perhaps she had overstepped the bounds of their friendship, which made it all the more surprising to see the sheen of tears in his eyes.

“Thank you,” he said. “You have always been a very kind friend.”

Something about his response disconcerted her. She laid a hand on his shoulder. “You get on with your reply. I’ll put up some anti-intrusion spells.”

Anti-intrusion spells were

immaterial in their situation: even those that could hold off a determined housebreaker were of no use against the might of Atlantis. But she wanted to give Kashkari some space to grieve, without her standing next to him.

She went into the adjoining room and pulled out her wand from her boot. No lamps had been lit in this room, but as soon as her fingers closed over the wand, she remembered that she still had Validus. Titus had given it to her before the battle in the desert, hoping that the blade wand would be a magnificent amplifier of her powers.

And it had been.

She hesitated over whether to call a bit of flame, decided against it, and murmured a few spells with Validus pointed at the window. The diamond-inlaid crowns along the length of the blade wand were barely visible in the feeble light that drifted in from the other room. The facets of the gems seemed to . . .

She opened her eyes wider. Were the crowns growing brighter and then fainter in turn? The second-lowest one was now perceptibly brighter than the rest, now the third lowest one, going up in an orderly procession, then coming down again.

“Kashkari.”

“Yes?” he answered immediately, his voice reflecting the tightness of her own.

“Extinguish the lantern and come here.”

The outer room fell into darkness. Kashkari arrived silently. “What’s the matter?”

“I need you to take a look at Validus.”

He took the wand from her. She waited, a nameless dread trickling down her spine.

“Is it always like this?” he asked, after a minute.

“I don’t know. The wand belongs to Titus. He gave it to me last night because he thought I might put it to better use.”

“Could it be a signal from him?”

“If it is, he has never told me about such a use for this wand.”

“Have you checked your tracer?”

Titus had a pendant that broke apart into a pair of tracers. At the moment he held one, and Iolanthe the other.

“I have and I can’t tell the difference.” Titus was so far away that the tracer had been ice-cold for hours.

Kashkari was silent for some time. “What does your gut say?”

She was slow to answer, not wanting to speak aloud the words gnawing at her nerves. “That it can’t be good.”

Kashkari did not disagree, but moved closer to the window. She joined him there. The window opened onto a dim, quiet courtyard, illuminated only by light from the surrounding guest rooms.

He opened the window a crack and murmured something in a language she didn’t understand—Sanskrit, probably. She could just make out something dark taking shape in his palms. And then it flapped its wings and took off—a bird made of the very shadows of the night, it seemed.

“Our canary, so to speak,” explained Kashkari.

She had been a canary once, one of the most harrowing experiences of her life. “What dangers would it alert us to?”

“Anything that might imperil a flying entity, or so I hope.” He released several more such birds.

In front of him, a few specks of light came to be. Iolanthe was confused for a moment until she realized they weren’t stray bits of fire that she didn’t remember summoning, but tiny representations of the birds.

“Nice piece of wizardry,” she whispered.

“My brother is working on a far more ambitious version—should he succeed, we’d be able to see what the birds are seeing, a three-dimensional rendering of their surroundings.”

One of the birds disappeared in a microscopic shower of sparks. “Did it fly into something?”

“No, they avoid mundane obstacles like houses and pedestrians—even cats.”

He bent forward, so as to be level with the smidgens of lights that stood for the remaining shadow canaries.

A second bird exploded, followed by a third. She turned cold: the danger was not at Titus’s end, but theirs.

“They are destroyed when they fly higher,” said Kashkari, his voice clenched.

“By what?”

“I don’t know. But it’s fairly certain that we also can’t fly high, at least not nearby.”

“Why is there such a thing overhead? Do you—do you think Atlantis knows we are here?”

“It might, if the wand has been broadcasting its location.”

His words hung between them. Her throat burned with the very idea of such a betrayal. How could Titus’s wand, of all things, turn on them?

She was shocked to hear herself speak in an even, collected tone. “If that’s the case, then we had better be on the move.”

How long had they been in Cairo? In the guest house? Was it long enough for Atlantis to pinpoint their location?

“Leave the wand behind,” said Kashkari.

“But it once belonged to Titus the Great.” A priceless heirloom, not just for the House of Elberon, but for the entire Domain.

“It will be the end of you if you keep holding on to it.”

She bit the inside of her cheek. Then she held the wand aloft with a levitation spell and sent a sphere of lightning crashing toward it. For a fraction of a moment, everything inside the room stood out in sharp relief: the wand, Kashkari’s startled gaze, the line where the wall met the ceiling.

When she grabbed hold of the wand again, it was hot to the touch and smoking a little, but as far as she could tell, the diamond-inlaid crowns were no longer changing in luminosity, however subtly.

“Let’s go,” she said.

They left on a single carpet—Kashkari’s skills were a better match for the close confines of an urban district. Iolanthe held on to him from behind and kept her gaze upward, but she couldn’t see anything overhead, other than a narrow alley of dark sky, between the nearly kissing top stories of the houses to either side.

The air smelled of spent coal, bread, and a faint undernote of donkey droppings. The night was becoming cooler, a breeze from the sea pushing out the residual heat from the day. Kashkari steered carefully, inching them forward.

A movement caught in the corner of her eye. But when she looked to the side, she didn’t see anything. What was it? A reflection on a still-open window, which meant the object was . . .

“Go! Fast as you can,” she hissed.

The thing behind them was a miniature armored chariot, a pod scarcely bigger than the desk in her room at Mrs. Dawlish’s and almost the exact same shadowy color as the night. A pair of claws, attached to long cables, shot out from the pod’s snout, aimed directly at her.

The carpet accelerated with a leap and took a sharp right turn tilted almost perpendicular to the street—only to careen headlong into the embrace of another pair of big claws.

Kashkari grunted and steered the carpet even lower, flattening it out completely. They passed under the incoming pod with scarcely an inch to spare above their heads.

Iolanthe sent a bolt of lightning toward the sky—their location had already been discovered, might as well find out what exactly loomed overhead. A gossamer net shimmered briefly, a thin, beautifully latticed web that stretched as far as she could see.

Fortune shield her. Had they covered all of Cairo?

Ahead three more vehicles blocked the way. Two pursued them from behind, and the way up was sealed.

She threw a barrage of opening spells at the nearest house. Kashkari banked a stomach-lurching turn. They shot past the front door into a dark, narrow passageway and saw the stairs just in time to pull up the carpet. At the top of the stair landing, Kashkari made her squeal by turning the carpet completely sideways. They fitted through a slender window—and barely avoided becoming caught in a tangle of laundry lines outside.

A half-wet sleeve—or was it a trouser leg?—slapped her on the shoulder as they dipped into an alley no wider than her arm span.

“What if they have sealed off the entire city?” Fear soaked her question. What if all they managed, by evading the armored pods, was to run into that lacy, bird-killing web somewhere down the road?

More laundry. Was

that a donkey they avoided? Another pod barreled toward them. Kashkari jerked the carpet into a door Iolanthe opened for him. Strange odors assailed her nostrils—had they plowed into a gathering of hashish smokers? The faces that turned toward them, from low divans all around the walls, wore expressions of vague surprise rather than outright astonishment.

Then they were out another door into a walled garden. Kashkari kept the carpet as low as possible as they went over the walls—she could feel the jagged bits of glass embedded at the top of the wall scraping the bottom of the carpet. Thank goodness they were on a battle carpet and it was thick.

“Do you dare go back to Eton?” came Kashkari’s question, between a sudden dip and another tight turn.

A pod dropped down from nowhere. Its claws hurtled toward Iolanthe with terrifying speed. She yelled as she sent the water of a nearby well toward the claws—as ice, freezing them so that they could not close around her person.

“Just get us out of here!”

More twisting, ribbon-narrow alleys, more humble houses flown right through. The streets became wider, straighter, illuminated by gas lamps; the houses to either side sprouted balconies and elegant latticework windows and wouldn’t have looked out of place along a major boulevard in Paris.

Kashkari seem to know the neighborhood well: she could hear the bustle and crowd on the next street, but the one down which they charged was entirely empty of pedestrians, its residents either eating dinner genteelly inside or having gone to the busy thoroughfare for their evening entertainment.

“See that building? That’s the opera house. Don’t think the season has quite started yet, so it should be empty. Open all the windows and doors as you did before. Do you have anything that can look somewhat like us, to act as dummy doubles?”

She thought wildly. “I’ve a tent. It can take various shapes.”

“Have it ready.”

She fished the tent out of her satchel—the tent that had served as Titus’s and her shelter during their days in the desert. They shot into a side door and came to a sudden halt that almost threw her off. Kashkari jumped down from the carpet and motioned her to do the same.

_preview.jpg) Claiming the Duchess (Fitzhugh Trilogy Book 0.5)

Claiming the Duchess (Fitzhugh Trilogy Book 0.5) The Art of Theft

The Art of Theft The Magnolia Sword: A Ballad of Mulan

The Magnolia Sword: A Ballad of Mulan A Study In Scarlet Women

A Study In Scarlet Women The Hollow of Fear

The Hollow of Fear The Magnolia Sword

The Magnolia Sword Beguiling the Beauty ft-1

Beguiling the Beauty ft-1 The Heart is a Universe

The Heart is a Universe The Hidden Blade: A Prequel to My Beautiful Enemy (Heart of Blade)

The Hidden Blade: A Prequel to My Beautiful Enemy (Heart of Blade) Ravishing the Heiress ft-2

Ravishing the Heiress ft-2 The Immortal Heights

The Immortal Heights The Hidden Blade

The Hidden Blade Ravishing the Heiress

Ravishing the Heiress Tempting the Bride

Tempting the Bride The Luckiest Lady in London

The Luckiest Lady in London The Bride of Larkspear: A Fitzhugh Trilogy Erotic Novella

The Bride of Larkspear: A Fitzhugh Trilogy Erotic Novella Claiming the Duchess

Claiming the Duchess The One in My Heart

The One in My Heart His At Night

His At Night A Dance in Moonlight

A Dance in Moonlight A Conspiracy in Belgravia

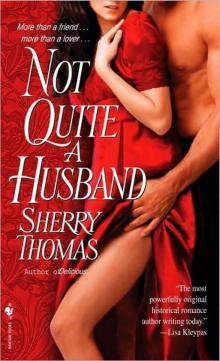

A Conspiracy in Belgravia Not Quite a Husband

Not Quite a Husband